Thúy Kiều (Grace) is a travel blogger and content contributor for Loop Trails Tours Ha Giang. She holds a bachelor’s degree in Sustainable Tourism from Vietnam National University, Hanoi, and has a strong passion for exploring and promoting responsible travel experiences in Vietnam’s northern highlands.

Tucked into a valley about 3 kilometers from Dong Van town sits a structure that feels wildly out of place—a Chinese-style fortress built by a Hmong opium lord who controlled this corner of northern Vietnam for nearly a century. Vuong Palace isn’t a palace in the European sense. It’s something stranger and more specific: a fortified family compound that served as the seat of power for the “Hmong King,” a title the Vuong family never officially held but absolutely earned through wealth, influence, and strategic ruthlessness.

Most travelers riding the Ha Giang Loop pass through Dong Van without realizing this place exists. That’s a shame, because Vuong Palace offers something rare—a concrete connection to the messy, complicated history of this region that goes beyond scenic viewpoints and ethnic minority photo opportunities. The building itself is impressive: stone walls, elaborate woodwork, defensive features built into seemingly decorative elements. But the real story is what it represents: the opium trade, French colonial manipulation, ethnic power dynamics, and the strange autonomy this remote area maintained even under foreign occupation.

This guide covers everything you need to visit Vuong Palace intelligently: the history that actually matters, what you’re looking at when you walk through the rooms, how to get there, how much time to budget, and how it fits into a broader Ha Giang Loop itinerary.

Learn more: Ha Giang Loop Tours

Learn more: organized Ha Giang Loop tour

The Ha Giang Loop delivers endless mountain scenery, and after two or three days, viewpoints start to blur together. Vuong Palace breaks that pattern. It’s a cultural and historical site with actual depth, not just another photo opportunity with limestone peaks in the background.

First, it’s one of the few places on the loop where you get meaningful context about the region’s history. Most homestays and tour guides will tell you about Hmong culture in general terms—traditional clothing, farming practices, festivals. Vuong Palace shows you a specific historical narrative: how one family accumulated enormous wealth and power, how they navigated between Chinese influence and French colonial control, and how that power ultimately collapsed when the Communist government took over.

The architecture alone justifies the visit. This is a 100-year-old mansion built with materials hauled across mountains by hand, constructed by craftsmen brought from China, designed to impress and intimidate. The level of detail—carved wooden panels, stone courtyards, the strategic placement of rooms for defense—shows serious money and serious ambition. You don’t see buildings like this anywhere else in Ha Giang province.

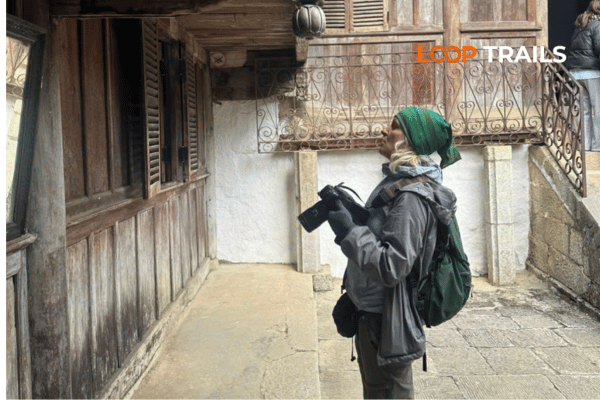

For photographers, Vuong Palace offers different subject matter than the usual Ha Giang shots. Instead of terraced fields and mountain roads, you’re working with architecture, textures, interior spaces, and the interplay between the fortress and the surrounding landscape. The stone walls against the karst mountains make for striking compositions.

Practically speaking, Vuong Palace is an easy addition to most loop itineraries. It’s a short detour from Dong Van town, requires maybe 1-2 hours total including travel time, and breaks up the riding nicely if you’re spending a night in Dong Van. It’s also a good bad-weather option—when Ma Pi Leng Pass is socked in with fog and there’s nothing to see, you can visit Vuong Palace and actually learn something.

The site is managed professionally with informational signs in Vietnamese, English, and Chinese. You can explore independently or hire a local guide at the entrance for deeper historical context. Either way works, but having someone explain what you’re looking at adds significant value.

One warning: if you’re looking for pristine, untouched historical sites, Vuong Palace has been renovated and “improved” over the years. Some restoration work is authentic and necessary. Some additions feel touristy and out of place. You need to look past the newer elements to appreciate what’s actually there.

Learn more: Ha Giang Loop for Beginers

The Vuong story starts in the mid-1800s with Vuong Duc Chinh, a Hmong man who recognized that controlling opium production in this region meant controlling serious wealth. The climate and terrain around Dong Van were perfect for growing poppies, and demand—both within China and through French colonial trade networks—was enormous.

Vuong Duc Chinh didn’t invent the opium trade here, but he organized it. He consolidated production among Hmong farmers, established processing operations, controlled the trade routes through the mountains, and positioned himself as the necessary middleman between producers and buyers. Within a generation, the Vuong family had accumulated wealth that dwarfed anything local chiefs or village leaders could touch.

First Generation (Vuong Duc Chinh): Built the initial wealth through opium trade consolidation. Established relationships with Chinese merchants and local Hmong communities. Set up the family’s position as regional power brokers.

Second Generation (Vuong Duc Trinh): Expanded operations and navigated the increasing French colonial presence. The French, who nominally controlled this territory, found it easier to work through powerful local intermediaries than try to administer these remote mountains directly. Vuong Duc Trinh became that intermediary—collecting taxes, maintaining order, controlling trade, all while the French looked the other way on the opium business because it was profitable for everyone involved.

Third Generation (Vuong Chinh Duc): Started construction of the palace around 1902. This is the generation that decided to build something permanent and impressive—a physical manifestation of the family’s power. The palace took several years to complete, with materials imported from China and craftsmen brought in specifically for the project.

Fourth Generation (Vuong Chi Sinh and Vuong Chi Thanh): Inherited the completed palace and tried to maintain the family’s position through increasingly turbulent times—the fall of the Qing dynasty, French colonial wars, the rise of Vietnamese nationalism, and eventually the Communist revolution. They failed. When the Communists took full control of northern Vietnam in the 1950s, the Vuong family’s autonomous little kingdom ended. The opium trade was shut down, the wealth was confiscated or fled with family members to China, and the palace became government property.

Let’s be direct: the Vuong Palace exists because of the opium trade. The wealth that built it came from controlling poppy cultivation and opium processing across the Dong Van plateau. This wasn’t small-scale farming—this was an organized, multi-village operation producing substantial quantities for export.

The French colonial government officially prohibited opium in some contexts while profiting from it in others. In practice, they taxed the trade and worked through local power brokers like the Vuong family. It was a mutually beneficial arrangement: the French got revenue and administrative control without having to actually govern these mountains directly, and the Vuong family got legitimacy and protection for their business operations.

By the 1920s-1930s, the Vuong family controlled not just the opium trade but also significant agricultural land, had political authority over dozens of villages, and maintained their own armed men for security and enforcement. They were essentially running a small independent state within nominal French territory.

The Vuong family was never formally granted any royal title. “Hmong King” (Vua Mèo in Vietnamese, which is actually a somewhat derogatory term) was a label used by outsiders—Vietnamese, French, Chinese—to describe the family’s regional dominance. Among Hmong communities, the Vuong family’s status was more complex. They were respected for their wealth and power, but also resented for the control they exercised and the way they positioned themselves above other Hmong people.

The title stuck, though, and over time it became part of the palace’s identity. Today, tourist materials lean into it heavily because it sounds dramatic and sells the attraction better than “well-preserved opium lord’s mansion.”

When the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (Communist government) consolidated control over the north in the 1950s, the Vuong family’s autonomous power became untenable. The new government had zero interest in preserving feudal-style local dynasties or tolerating opium production. Some family members fled to China. Others stayed and lost their status and wealth. The palace was confiscated and used for various government purposes before eventually being recognized as a historical site and opened to visitors.

The story has a certain inevitability to it. The Vuong family’s power was built on a specific set of conditions—geographic remoteness, weak central government control, the profitability of opium, French colonial priorities. When those conditions changed, the dynasty had no foundation to stand on.

Learn more: Ha Giang Loop route and itinerary

Vuong Palace (also called Vuong Chi Sinh’s Old House or Dinh Vuong) is located in Sa Phin Valley, about 3 kilometers southwest of Dong Van town. The palace sits at the base of a valley surrounded by karst mountains, with the settlement of Sa Phin spread out nearby.

GPS coordinates: approximately 23.2719° N, 105.3542° E

Most visitors access the palace from Dong Van, which is a standard overnight stop on the Ha Giang Loop. From Dong Van’s town center, you’re looking at a 5-10 minute ride by motorbike.

The route is straightforward: head southwest out of town on the main road (QL4C) in the direction you came from if you arrived from Meo Vac or Yen Minh. About 2 kilometers from town, you’ll see clear signage pointing to Vuong Palace on your right. Turn onto this side road and follow it for about 1 kilometer to the palace parking area.

The road to the palace is paved and in good condition. No technical riding required—just a gentle valley road.

If you’re coming from other directions on the loop:

Signage is decent. There are multiple signs in Vietnamese, English, and Chinese directing you to “Dinh Vuong” or “Vuong Family House.”

If you’re on an organized Ha Giang Loop tour (Easy Rider, jeep, or group tour), Vuong Palace is often included as a standard stop, especially if your itinerary overnights in Dong Van. Confirm with your guide or tour operator whether it’s included or if it’s an optional add-on.

For Easy Rider guides, this is typically an easy request even if it’s not in the original plan—it’s close to Dong Van and doesn’t add much time to the day.

Parking at the palace is straightforward. There’s a dedicated lot that can accommodate motorbikes, cars, and even tour buses. No parking fees as of current information, though this could change.

Learn more: Ha Giang Loop 4 Days 3 Nights

Vuong Palace is a hybrid. It combines traditional Chinese architectural elements with local materials and defensive features specific to this region’s history of banditry and conflict. The result is something that looks grand and refined from a distance but reveals its fortress nature up close.

The palace complex is organized around multiple courtyards—a classic Chinese architectural approach. You enter through a main gate, which leads to an outer courtyard, which then opens into additional courtyards surrounded by living quarters, storerooms, and functional buildings.

The entire compound covers roughly 1,120 square meters and includes more than 60 rooms. That’s substantial by any standard, but especially for a remote mountain location where every building material and piece of furniture had to be transported by foot or horseback.

The layout is hierarchical. Public spaces and areas for receiving guests are near the front. Family living quarters are deeper in. Storage areas (including the opium storage rooms) are in the back sections with restricted access.

The architecture borrows heavily from southern Chinese mansion styles—particularly Hakka and Cantonese influences. You see this in the roof design with its curved eaves, the wooden column-and-beam construction, the courtyard organization, and the decorative elements.

But it’s adapted for local conditions. The stone walls are thicker than typical Chinese mansions because they serve a defensive purpose. The roof tiles are heavier and more securely fastened to handle the wind and weather of this elevation. The building sits low and solid rather than light and elevated, because it needed to be a fortress as much as a residence.

Local Hmong building techniques appear in some of the detail work and in how the structure integrates with the landscape. The craftsmen may have come from China, but the laborers were local, and they brought their own knowledge to the construction.

Make no mistake—this is a fortified compound. The Vuong family needed to defend their wealth and position against rival factions, bandits, and potential uprisings.

The walls are thick stone construction, too high to easily scale, with limited entrances that could be secured and defended. Some walls exceed one meter in thickness.

The gate is the only main entry point, deliberately narrow to prevent multiple attackers from entering simultaneously. It’s positioned so that anyone approaching is visible from multiple points within the compound.

The watchtower at the rear of the complex gave guards a clear view of approaching threats and allowed for defensive positioning.

Windows in the outer-facing walls are small and positioned high, making it difficult for attackers to see in or shoot through while still allowing light and ventilation.

Internal layout creates choke points and defensive positions throughout the compound. Even if someone breached the gate, they’d have to navigate through multiple courtyards and passages where defenders could control movement.

These aren’t subtle features. When you walk around the palace, it’s obvious that security was a primary concern in the design.

The palace was constructed primarily from:

The construction reportedly took 6-8 years and required significant labor. Stories (possibly exaggerated but plausible) claim that materials were carried across mountain passes by porters, with some journeys taking weeks.

The level of craft is high. Wooden beams feature intricate carvings—dragons, phoenixes, floral patterns—that have survived a century with minimal degradation. Stone courtyards are precisely laid. The whole thing was built to last and to impress.

Learn more: Ha Giang Loop for Families & Groups

Vuong Palace is a self-guided experience with informational signs, though local guides are available at the entrance if you want deeper context and stories that aren’t on the plaques.

You enter through the substantial wooden gate into the first courtyard. This is where guests and visitors would have been received, where business was conducted, and where the Vuong family displayed their status to outsiders.

The courtyard is paved with stone, surrounded by covered walkways with wooden pillars. Look at the woodwork—the beam carvings are original and show the level of detail the Vuong family demanded.

This is the reception area where the family head would meet with visitors, conduct negotiations, and handle administrative matters. The hall features:

The hall feels formal and imposing, which was the point. This was where the “Hmong King” received tribute, settled disputes, and demonstrated power.

Behind the main hall, you’ll find the family’s private living spaces. These rooms are smaller and more intimate than the public areas:

Many rooms still contain period furniture—not all original to the Vuong family, but appropriate to the era and style. Some pieces are reproduction, some are authentic items collected from other sources.

The palace doesn’t hide its opium connection. Several rooms in the back section are labeled as opium storage areas where processed opium was kept before being transported for sale.

These rooms are small, windowless, and secure—designed to protect valuable inventory. There’s nothing particularly dramatic about them (no opium remnants or tools on display), but they’re an honest acknowledgment of what funded this entire operation.

The working sections of the palace give you a sense of daily operations. The kitchen is large with multiple cooking stations—this was a household that employed staff and entertained guests regularly.

You’ll see:

These areas are less decorative but more revealing about how the palace actually functioned as a living space.

At the rear of the complex stands a two-story tower that served as a lookout point. You can climb up (stairs are narrow and steep—watch your footing) for views over the valley and surrounding area.

From the top, you understand the strategic positioning of the palace. It sits in a valley with mountain walls on multiple sides, visible approaches, and natural defensive advantages. The Vuong family chose this location carefully.

Multiple courtyards connect the different sections of the palace. These open spaces served various functions—drying crops, conducting outdoor work, gathering spaces for household activities.

The courtyards also demonstrate wealth. Paving an entire courtyard with cut stone was expensive and labor-intensive. Having multiple courtyards showed that the Vuong family had resources to spare.

Be aware that Vuong Palace has undergone restoration and reconstruction over the decades. Some of what you see is original, some has been rebuilt following original designs, and some has been added for tourist purposes.

Definitely original: The stone walls, basic structure, courtyard layout, main wooden framework, carved beams and decorative panels

Possibly restored: Roof tiles (many replaced over the years), some furniture, paint and decorative elements, flooring in some areas

Clearly modern: Some signage, the ticket booth, the parking area, bathroom facilities

This doesn’t diminish the site’s value, but it’s worth understanding that you’re not looking at an untouched 100-year-old building. You’re looking at a well-maintained historical site that’s been preserved for visitors.

Learn more: Ha Giang in September & October

Vuong Palace is open year-round, and because it’s an architectural/historical site rather than a landscape viewpoint, weather matters less than it does for places like Ma Pi Leng Pass or Heaven Gate.

That said, some seasons offer better experiences:

September to November: Peak season for the Ha Giang Loop. The weather is stable, temperatures are comfortable for walking around the palace grounds, and lighting is good for photography. Expect more visitors, especially on weekends. The palace can feel crowded when multiple tour groups arrive simultaneously.

December to February: Cold season. Temperatures can drop significantly, and Dong Van sits at high elevation. The palace is interesting in any weather, but walking around stone courtyards in 5-10°C temperatures is less pleasant. Upside: far fewer tourists. You might have the place nearly to yourself on a weekday.

March to May: Shoulder season with pleasant temperatures and good lighting. Fewer crowds than autumn but more than winter. This is actually an ideal time if you can manage the timing. The surrounding valley is green, weather is unpredictable but often clear, and the palace grounds are comfortable to explore.

June to August: Monsoon season. Rain doesn’t prevent visiting—the palace has covered walkways and many interior spaces—but it does make photography challenging and reduces the appeal of wandering the courtyards. The surrounding landscape is incredibly lush if you’re into that aesthetic.

Time of day matters less for Vuong Palace than for viewpoints, but afternoon light (2pm-4pm) is better for photography than harsh midday sun. Early morning has soft light but you’re more likely to encounter fog in the valley during certain seasons.

Most visitors hit Vuong Palace in the morning (9am-11am) or late afternoon (3pm-5pm) as part of exploring Dong Van. Midday is quietest if you want to avoid groups.

Learn more: Ha Giang Loop Insurance

As of the latest available information, entrance fees are quite reasonable:

These fees are subject to change, so verify current pricing when you visit. Payment is cash only at the ticket booth near the entrance.

Opening hours: Approximately 7:00 AM to 5:30 PM daily. The palace is open every day including weekends and most holidays, though this can vary during Tet (Vietnamese New Year) or other major celebrations.

Arrive at least 30-45 minutes before closing if you want adequate time to explore. Guards will start ushering people out as closing time approaches.

Local guides: Available at the entrance for 100,000-150,000 VND for a group (not per person). Guides speak Vietnamese and varying levels of English and Chinese. The quality varies—some are knowledgeable and engaging, others give rote information. If you care about deeper historical context, it’s worth the cost. If you prefer exploring independently and reading the informational signs, you can skip the guide.

Facilities:

No restaurant on-site. If you want proper food, head back to Dong Van town.

Learn more: Ha Giang Loop 3 Days 2 Nights

Budget 1-2 hours for a thorough visit.

If you’re rushing: 30-40 minutes lets you walk through the main sections, see the courtyards, take a few photos, and get a basic sense of the place. This is better than skipping it entirely but doesn’t do the site justice.

Standard visit: 60-75 minutes gives you time to explore all the rooms, read the informational signs, appreciate the architecture, climb the watchtower, and take decent photos without feeling rushed. This is what most visitors should plan for.

Deep dive: 90-120 minutes if you hire a guide, want to photograph everything properly, enjoy historical sites, or just prefer to move slowly and absorb the atmosphere. There’s enough detail and story here to justify this time if you’re genuinely interested.

The palace isn’t enormous, so you won’t need half a day. But it’s dense with detail and historical context that rewards careful attention.

Combining with other Dong Van area attractions: Most riders structure their day to include Vuong Palace plus other stops:

This pacing works well and doesn’t feel rushed if you start reasonably early.

Learn more: Ha Giang to Cao Bang

Dong Van is the Ha Giang Loop’s northernmost major town and serves as a hub for several worthwhile stops. Vuong Palace fits naturally into a broader exploration of the area.

The historic center of Dong Van town features French colonial architecture, traditional buildings, and a weekend market that draws Hmong traders from surrounding villages. It’s a 10-minute ride from Vuong Palace and worth 30-60 minutes of wandering.

The old quarter has been renovated (sometimes over-renovated in ways that feel touristy), but it still has character. Look for the old French buildings with shuttered windows, the market square, and the small alleyways where locals actually live and work.

Sunday is market day, when the town fills with Hmong people in traditional dress selling produce, livestock, and handmade goods. If your loop timing puts you in Dong Van on Saturday night/Sunday morning, adjust your schedule to see the market—it’s worth it.

Learn more: Lung Cu Flag Tower Guide

About 25 kilometers north of Dong Van sits Vietnam’s northernmost point, marked by a massive flag tower on top of Lung Cu peak. The ride up is spectacular—winding mountain roads with panoramic views—and the symbolism of standing at the country’s geographic top appeals to many visitors.

The tower itself is fine but not architecturally significant. You’re there for the views and the achievement of reaching the northernmost accessible point. Budget 2-3 hours round trip from Dong Van including the ride and time at the tower.

Combining Vuong Palace and Lung Cu in one day works if you start early. The route: Dong Van → Vuong Palace (morning) → Lung Cu (midday/early afternoon) → return to Dong Van or continue toward Meo Vac depending on your itinerary.

If you’re coming to Dong Van from Meo Vac or heading that direction, Ma Pi Leng Pass is mandatory. It’s the most dramatic viewpoint on the entire loop—sheer cliffs, the Nho Que River far below, the road carved into the mountainside.

Ma Pi Leng is 20-25 kilometers from Dong Van and takes 45-60 minutes to ride with stops. Most people hit it as a separate half-day activity rather than trying to combine it with Vuong Palace, but your schedule might allow for both depending on pacing and daylight.

Several Hmong villages surround Dong Van and are accessible by motorbike on small roads. These visits offer glimpse of traditional life—farming, textile weaving, daily routines.

The challenge is doing this respectfully. Villages aren’t museums. People are going about their lives, and having foreigners wander through with cameras can be intrusive. If you’re interested in village visits, go with a local guide who has relationships and can facilitate appropriate interactions.

For most Ha Giang Loop riders:

Don’t try to cram too much into one day. The loop is about enjoying the ride and the places, not checking boxes as fast as possible. Vuong Palace deserves focused attention rather than being one rushed stop among five.

Learn more: Ha Giang Loop Cost & Tips

Dong Van town is the logical base for visiting Vuong Palace, sitting just 3 kilometers away. The town has evolved to accommodate loop travelers with a range of accommodation options.

Multiple Hmong homestays operate in and around Dong Van. These are usually family homes that have set aside rooms for guests, offering:

Expect to pay 100,000-150,000 VND per person per night including meals. Quality varies significantly—some homestays are well-set-up with comfortable beds and cleaner facilities, others are quite basic. Ask other travelers or check recent reviews if you’re particular.

The trade-off for simplicity is authenticity. You’re eating with a Hmong family, sleeping in a traditional house, experiencing daily life firsthand. For many travelers, this is the highlight of the loop.

Dong Van has numerous small guesthouses offering private rooms with varying comfort levels:

These provide more privacy and slightly better facilities than homestays without the cultural immersion. Breakfast may or may not be included—confirm when booking.

A few mini-hotels in Dong Van cater to travelers wanting more comfort:

Expect 400,000-700,000 VND per room. By Vietnamese city standards these are budget hotels, but in Dong Van they’re the upscale option.

Dong Van is small enough that showing up without a reservation usually works except during peak weekends in September-November. During those busy periods, having a booking helps, especially for better properties.

If you’re on an organized tour or with an Easy Rider guide, accommodation is typically included or they’ll handle bookings. If you’re self-driving, you can:

Some riders skip Dong Van entirely and overnight elsewhere:

Dong Van offers the most accommodation choices, the most developed tourist services, and the most convenient access to Vuong Palace, Lung Cu, and the old quarter. Unless you have specific reasons to stay elsewhere, it’s the practical choice.

Learn more: Ha Giang Loop Easy Rider

Some things that will make your Vuong Palace visit smoother:

Wear appropriate footwear. The courtyards are stone, some floors are uneven, the watchtower stairs are steep. Sneakers or hiking shoes work better than flip-flops or sandals.

Bring cash. Entrance fees are cash only, no cards accepted. If you’re hiring a guide, that’s also cash. The small shop takes cash. There’s no ATM at the palace—get cash in Dong Van town before you visit.

Respect the site. This is a historical building, not a playground. Don’t climb on walls, touch fragile carved elements excessively, or move furniture for photos. Stay on marked paths and follow any posted rules.

Photography is allowed but be thoughtful. If other visitors are in a space, don’t monopolize it for elaborate photo shoots. If staff or guides are present in a room, ask before including them in your shots.

The palace tells a complicated story. The Vuong family’s wealth came from opium, which caused immense social harm. They maintained power through means that weren’t always benign. The site doesn’t glorify this—it presents history. Engage with that complexity rather than treating it as just another cool building.

Language: Signage is in Vietnamese, English, and Chinese. The English is functional but sometimes awkwardly translated. If you hire a guide and don’t speak Vietnamese, confirm their English level before committing—some guides know the stories but struggle with English explanation.

Bathrooms are basic. Use facilities in Dong Van town before or after your visit if you prefer Western toilets or cleaner conditions.

Weather protection: The palace has covered walkways, but you’ll be outdoors in courtyards frequently. Bring sun protection (hat, sunscreen) for hot days, rain gear if it looks threatening, and a light jacket for cold season visits.

Timing with groups: If you arrive and multiple tour buses or jeep groups are there, consider waiting 20-30 minutes for them to move through. The palace is more enjoyable when you can move at your own pace without navigating around large groups.

Drone flying: Check current regulations. Some historical sites prohib’t drones. If allowed, be respectful of other visitors and don’t fly over areas where people are trying to enjoy the space without buzzing overhead.

Purchasing souvenirs: A few vendors sell handicrafts and textiles near the entrance. Prices are negotiable. Quality varies—some items are locally made, others are mass-produced. If you’re buying Hmong textiles, look for handwoven pieces with tight stitching and natural dyes rather than factory-printed fabric.

Combining with meals: No food service at the palace. Plan to eat before or after in Dong Van. The town has several local restaurants serving phở, bún, cơm, and other Vietnamese staples. Meals run 30,000-60,000 VND. Don’t expect English menus or extensive options, but the food is good and authentic.

Learn more: Ha Giang Jeep Tours

Is Vuong Palace worth the detour from the main loop route?

Yes, especially if you’re interested in history and architecture beyond just scenic viewpoints. It’s a minimal detour—3 kilometers from Dong Van—and adds meaningful context to your Ha Giang experience. If you’re completely focused on mountain scenery and have zero interest in historical sites, you might skip it. But most travelers appreciate the change of pace.

Can you visit without a guide?

Absolutely. The palace has English signage explaining what you’re looking at, and the layout is straightforward enough to explore independently. A guide adds depth and stories that aren’t on the signs, but it’s not necessary for a satisfying visit.

Is the palace wheelchair accessible?

No. There are steps throughout, uneven stone surfaces, narrow passages, and a watchtower with steep stairs. Visitors with mobility limitations will struggle with full access. The outer courtyards are somewhat accessible, but interior spaces are not.

How does Vuong Palace compare to other historical sites in Vietnam?

It’s unique in northern Vietnam for its specific combination of Chinese architecture, Hmong cultural context, and opium trade history. You won’t find another site quite like it in the region. Compared to imperial sites in Hue or ancient towns like Hoi An, it’s smaller and less grand, but it tells a different, more localized story.

Can you stay overnight at Vuong Palace?

No overnight accommodation at the palace itself. It’s a daytime visitor site only. Stay in Dong Van town (3km away) or nearby villages.

Are there any festivals or special events at Vuong Palace?

The palace sometimes hosts cultural events or festivals, particularly during Tet (Lunar New Year) or Hmong cultural celebration periods. These aren’t regular occurrences and aren’t heavily advertised to tourists. If you happen to visit during one, it’s a bonus, but don’t plan your trip around it.

What’s the best way to reach Vuong Palace if I’m not riding a motorbike?

From Dong Van town, you can:

Most practical is hiring a xe ôm if you’re not on your own bike.

Is there phone signal and WiFi?

Phone signal (Viettel, Mobifone) works in the area, though it can be spotty inside the thick-walled palace buildings. No WiFi at the site. If you need internet, use your phone data or wait until you’re back in Dong Van town where many accommodations offer WiFi.

Learn more: Nho Que River & Tu San Canyon

The entrance fee (currently around 30,000 VND) covers access to the entire palace complex including all rooms, courtyards, and the watchtower. It doesn’t include a guided tour—guides are hired separately at the entrance if desired. The fee helps maintain the site and pays for basic upkeep.

Approximately 3 kilometers, which translates to 5-10 minutes by motorbike depending on your pace. The road is easy and well-signed. If walking, budget 45-60 minutes. Most visitors ride or hire transport rather than walking.

Yes, photography is permitted throughout the palace including interior rooms. No flash restrictions that I’m aware of, though using flash on old wooden carvings and artifacts isn’t recommended anyway. Some visitors prefer natural light for better quality photos. Video recording is also allowed.

Guides primarily speak Vietnamese. Many have working English—enough to convey the basic history and show you around, though fluency varies. Some guides speak Chinese, which makes sense given the palace’s history and the number of Chinese tourists who visit. Communication might require patience and gestures, but it’s manageable.

Yes, though young children might find it less engaging than adults. There are no interactive exhibits or child-specific attractions—it’s a historical building with rooms to walk through. Older kids interested in history or architecture will appreciate it. Main safety consideration is the watchtower stairs, which are steep. Supervise children carefully on those.

Construction began around 1902 under Vuong Chinh Duc and took approximately 6-8 years to complete, finishing around 1908-1910. The building is therefore roughly 110-120 years old. It has been restored and maintained over the decades, so not everything you see is original to that construction period.

“Palace” is a somewhat generous translation. In Vietnamese, it’s often called “Dinh Vuong” (Vuong House/Residence) or “Nhà Cũ Vua Mèo” (Old House of the Hmong King). The “king” and “palace” terminology come from the family’s regional power and wealth rather than formal royal status. It stuck because it’s dramatic and helps market the site to tourists.

Most 3-4 day loop itineraries include an overnight in Dong Van, and Vuong Palace becomes an easy afternoon or morning add-on. Common structure: Day 2 or 3 of the loop, arrive in Dong Van from Meo Vac (via Ma Pi Leng Pass), visit Vuong Palace in the afternoon, overnight in Dong Van, continue the loop the next day toward Yen Minh or Quan Ba.

Casual comfortable clothing is fine. No strict dress code. Practical footwear (sneakers, hiking shoes) is more important than what you wear otherwise. If visiting during cold season (December-February), bring warm layers—Dong Van area gets genuinely cold and the stone palace doesn’t retain heat. In hot season, light clothing and sun protection.

Vuong Palace is the most significant and best-preserved example of this type of historical architecture in Ha Giang. There are other old buildings scattered across the province—some French colonial structures, traditional Hmong houses, old market buildings—but nothing on the scale or historical importance of Vuong Palace. It’s a unique site in the region.

Guides at the palace entrance offer site-specific tours, typically lasting 45-60 minutes. They’re hired specifically for the palace visit, not full-day services. The fee (usually 100,000-150,000 VND) covers just the palace tour. This is separate from Ha Giang Loop Easy Rider guides, who provide multi-day riding and touring services.

Late afternoon (2pm-4pm) offers warm, angled light that brings out the texture of the stone walls and creates interesting shadows in the courtyards. Morning light (8am-10am) is also good, softer and less harsh. Avoid midday sun (11am-1pm) when possible—the light is flat and creates hard shadows that don’t flatter architectural photography. Golden hour (just before sunset) can be beautiful but you’ll need to work quickly before the palace closes.

Only snacks and drinks from a small shop near the entrance—bottled water, soft drinks, packaged snacks, instant noodles. No restaurant or proper food service. Plan to eat meals in Dong Van town before or after your visit. The town has multiple local restaurants serving Vietnamese food at reasonable prices.

Contact information for Loop Trails

Website: Loop Trails Official Website

Email: looptrailshostel@gmail.com

Hotline & WhatSapp:

+84862379288

+84938988593

Social Media:

Facebook: Loop Trails Tours Ha Giang

Instagram: Loop Trails Tours Ha Giang

TikTok: Loop Trails

Office Address: 48 Nguyen Du, Ha Giang 1, Tuyen Quang

Address: 48 Nguyen Du, Ha Giang 1, Tuyen Quangit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Ut elit tellus, luctus nec ullamcorper mattis, pulvinar dapibus leo.

Facebook X Reddit Planning a Ha Giang Loop trip feels overwhelming at first. You’re scrolling through dozens of tour companies, comparing prices

Facebook X Reddit Cao Bang doesn’t show up on most Vietnam itineraries, and that’s part of its appeal. While Ha Giang has